He Pioneered Carbon Offsets to Save Tropical Forests. Now the Market Is Collapsing

Mike Korchinsky used offset credits to funnel millions of dollars to conservation projects. Now he’s fighting a crisis of confidence in the industry.

Mike Korchinsky gave up a lucrative career in management consulting after an “epiphany in the African bush,” turning to wildlife conservation and ultimately helping create one of the most popular tools for cutting carbon emissions.

Now, the 62-year-old from the California Bay Area is fighting to keep that business—and his own revenue stream—alive amid a crisis of confidence that is shaking the industry he helped start.

Korchinsky is a champion of carbon credits—a financial instrument that funnels private money to climate-friendly projects such as building solar farms or planting trees. Typically, such projects strive to stop global-warming emissions from hitting the atmosphere. The companies or individuals writing the checks get to claim they are reducing, or offsetting, their carbon footprints by the same amount.

Korchinsky’s company, Wildlife Works, issues credits from two big conservation projects—one in a savanna of southeast Kenya frequented by elephants and giraffes and another in a rainforest of the Democratic Republic of Congo that hosts bonobo and pangolin.

Wildlife Works projects include ones in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, top and left, and Kenya, at right. WILDLIFE WORKS; FILIP AGOO/WILDLIFE WORKS

Wildlife Works projects include ones in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, top and left, and Kenya, at right. WILDLIFE WORKS; FILIP AGOO/WILDLIFE WORKS  Wildlife Works projects include ones in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, top and left, and Kenya, at right. WILDLIFE WORKS; FILIP AGOO/WILDLIFE WORKS

Wildlife Works projects include ones in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, top and left, and Kenya, at right. WILDLIFE WORKS; FILIP AGOO/WILDLIFE WORKS

A growing number of skeptics say the math behind carbon credits is squishy and that the projects don’t do as much good for the climate as they report. Environmentalists are accusing companies of using credits to avoid the hard work of trimming emissions on their own, sometimes bringing lawsuits against those, such as Delta Air Lines, with big offset claims. Credit sales and prices have collapsed this year.

Last month, Korchinsky announced he was trying to regain buyers’ trust by helping start a new standard, or set of carbon-crediting procedures and best practices, for conservation projects. In a drastic move, the standard would eliminate the concept of offsets altogether—undercutting a prime reason companies buy carbon credits now.

Korchinsky says he is talking to companies about an alternate rationale for buying credits—one that still links purchases to a firm’s emissions, while avoiding the suggestion that procuring credits actually reduces them. How that would work exactly remains unclear, as does corporate appetite for credits without the “offset” component.

Korchinsky spent years trying to fund conservation activities in other ways, even enlisting celebrities such as Paris Hilton and Charlize Theron to hawk a Wildlife Works fashion line. Only carbon credits attract enough money for a full-fledged push to halt tropical deforestation, he says.

If the carbon market fails, “we squander the best opportunity we ever had for driving corporate finance to protect forests,” says Korchinsky.

A host of people are trying to fix the voluntary carbon market—so-called because companies and organizations that buy credits there aren’t required to do so, in contrast to government-regulated carbon markets such as the European Union’s Emissions Trading System. Other groups are proposing their own guidelines for how best to evaluate and use credits.

There are touches of Africa throughout the Wildlife Works offices in Mill Valley, Calif.

There are touches of Africa throughout the Wildlife Works offices in Mill Valley, Calif. There are touches of Africa throughout the Wildlife Works offices in Mill Valley, Calif.

There are touches of Africa throughout the Wildlife Works offices in Mill Valley, Calif.

Last year and the year prior were the voluntary market’s biggest ever, with around $2 billion each year in transactions, and predictions that carbon-credit sales could soon grow to more than $150 billion annually. Wildlife Works announced plans for at least 20 projects with projected credit sales of more than $2 billion.

But during the past several months, the bottom has fallen out of the market as buyers grapple with a tidal wave of new risks.

Carbon-credit trading volumes for the year through September were roughly a quarter of the same period in 2022, while prices were around half, according to data from the carbon-credit exchange run by environmental-commodities broker Xpansiv.

Several big buyers of Wildlife Works’ carbon credits have halted or delayed purchases, including Delta, which said it has moved away from offsets to decarbonizing operations, including investing in sustainable aviation fuel. The company says the lawsuit against it, which alleges Delta falsely claimed to be carbon neutral based on offsets, is without merit.

Meanwhile, governments are moving to take greater control of carbon rules and revenue, adding to the confusion.  Delta Air Lines said it has moved away from offsets to decarbonizing operations. PHOTO: ELIJAH NOUVELAGE/BLOOMBERG NEWS

Delta Air Lines said it has moved away from offsets to decarbonizing operations. PHOTO: ELIJAH NOUVELAGE/BLOOMBERG NEWS

Wildlife Works has delayed its expansion plans, fought against allegations that its credits aren’t worth what it says and canceled the issuance of $90 million worth of credits from its Congolese project after the government there implemented a new carbon-accounting system.

One of the most contentious issues is how to ensure the quality of credits, each of which is supposed to equal a metric ton of carbon emissions avoided, reduced or removed.

Forest conservation projects such as Wildlife Works’ are some of the toughest to parse. They issue credits based on how much deforestation would have occurred, and carbon dioxide released, if the project hadn’t existed—something impossible to predict with certainty.

Academics and journalists have accused such projects of shunting logging to other areas, or taking credit for tree growth that would have happened anyway. Some have said projects, including Wildlife Works’, haven’t given local communities the benefits they promised.

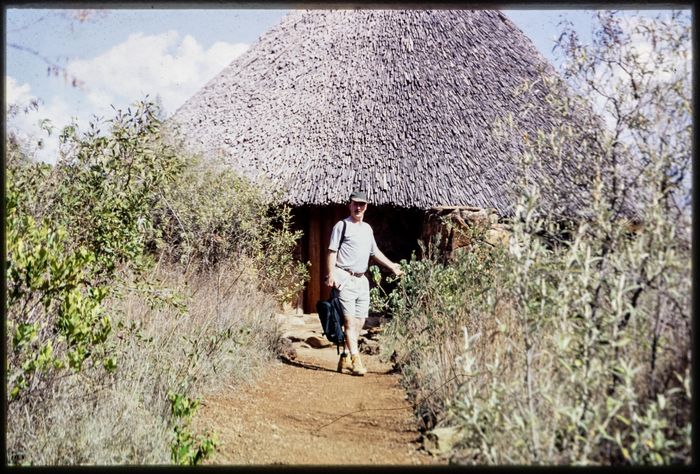

“We found poor quality under every rock we turned,” says Barbara Haya, director of a carbon-offsets research group at the University of California, Berkeley, of conservation projects in general. She is a co-author of a September report saying conservation projects generally vastly overestimate how many credits they should issue. Mike Korchinsky on his first trip to Kenya in 1996. PHOTO: MIKE KORCHINSKY

Mike Korchinsky on his first trip to Kenya in 1996. PHOTO: MIKE KORCHINSKY

Korchinsky has rebutted such claims, saying they don’t understand the science or ground conditions. He argues that getting money to projects that need it is more important than haggling over carbon math. But he also says calculating carbon credits isn’t an exact science.

“There’s not a meter running on a forest,” says Korchinsky. “It’s an imprecise world.”

Korchinsky set up Wildlife Works in 1997, after the sale of his business consulting firm. He used some of that money to set up a wildlife sanctuary in southeast Kenya, leasing a strip of land where ranchers grazed cattle.

If he could provide an alternate source of income for locals, they would let the area revert to a wilder state, and elephants, giraffes and lions would return, Korchinsky reasoned.

For years, Korchinsky struggled to deter poachers and fund the sanctuary and local communities with proceeds from a clothing factory Wildlife Works set up with local workers. He hired designers and marketers, sponsoring fashion shows in Paris and peddling merchandise at trendy venues such as the Sundance Film Festival.

Expenses were heavy, margins thin, and Korchinsky ended up subsidizing the sanctuary with his own dwindling savings.

In the mid-2000s, Korchinsky heard about carbon credits, and decided to give them a shot. At the time, there were no procedures set up for issuing credits tied to forest conservation. So Korchinsky and his team constructed their own—a 174-page methodology, now nearly double that length, covering everything from how to estimate deforestation from satellite photos to equations for calculating the carbon stored in trees versus shrubs and bushes.

Wildlife Works ended up selling the credits in 2011 to a South African bank that had pledged to become the first African lender to go carbon neutral. The sale totaled a bit less than $10 million dollars—a lot more money than T-shirt sales.

“We thought: there’s some there there,” says Korchinsky.

Around the same time, Korchinsky was approached by JR Bwangoy, a Congolese forestry professor who wanted to see whether carbon credits would work in the Congo.

Korchinsky says the Congo, with its political turmoil and civil wars, was on a list of countries where he didn’t want to work. The business center of the hotel in Kinshasa where he stayed had a sign warning against carrying AK-47s.

Bwangoy convinced Korchinsky to take a look anyway. “I showed him the forest, the people. It was tough at that time because the country was just coming out of war. In these villages there was basically nothing,” Bwangoy recalls.

The offices of Wildlife Works in Mill Valley, Calif.

The offices of Wildlife Works in Mill Valley, Calif.

That project is now Wildlife Works’—and the Congo’s—biggest, covering nearly 750,000 acres with 50,000 residents, including a pygmy tribe. The company says the project has halted logging, brought back elephants, improved the local standard of living and prevented millions of tons of carbon emissions.

Appetite for carbon offsets soared in 2021, amid a wave of government and corporate pledges to trim emissions and head off global warming. Wildlife Works’ fortunes picked up, too. In 2022, the Congo project alone sold $194 million in carbon credits.

Korchinsky says that is now all in jeopardy unless confidence is restored in the market.

“It’s troubling times,” he says.

Write to Phred Dvorak at